All My Parents: Seeking a Sense of Self in Family

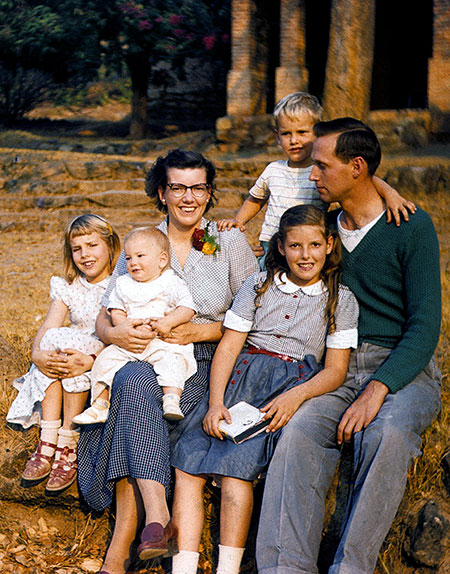

Children of missionaries in 1950s colonial Angola commonly left home for schooling. Nancy Henderson-James’s mother promised her it would be an adventure. For six years she lived away from her parents, in Angola, Southern Rhodesia, and the United States. The sudden end of her African life came in 1961, when war broke out in Angola. In her last two years of high school in Tacoma, Washington, she experienced culture shock and loss. By the end of high school, she had lived with five sets of adults who substituted as parents. Henderson-James loved her life in Africa, but in her forties, she realized she and other missionary children had paid a high price for their schooling. Her early years understandably made for sadness and loss of intimacy with the primary people in her life, despite well-meaning parental substitutes.

Children of missionaries in 1950s colonial Angola commonly left home for schooling. Nancy Henderson-James’s mother promised her it would be an adventure. For six years she lived away from her parents, in Angola, Southern Rhodesia, and the United States. The sudden end of her African life came in 1961, when war broke out in Angola. In her last two years of high school in Tacoma, Washington, she experienced culture shock and loss. By the end of high school, she had lived with five sets of adults who substituted as parents. Henderson-James loved her life in Africa, but in her forties, she realized she and other missionary children had paid a high price for their schooling. Her early years understandably made for sadness and loss of intimacy with the primary people in her life, despite well-meaning parental substitutes.

In All My Parents: Seeking a Sense of Self in Family, Henderson-James contemplates the impact her many parents had on her development and her relationship to family. Beginning with her own parents and grandparents, she delves into their lives and uncovers personality traits and passions that were passed along to her. Her substitute parents taught her new ways of being parents. Some surrogates were severe; others relished their assignment. Henderson-James met her future husband and his two sets of parents when she was twenty. They invited her into their homes while her parents still lived in Angola and they opened up unfamiliar aspects of America.

As Henderson-James and her husband raised their two sons, she wondered how to respond to her children. What should a parent do in a certain situation? What lessons from all her parents could she apply? In their old age, her parents moved to her town and she faced the task of rebuilding her relationship with them as she ushered them toward death.

A return to Angola after an absence of forty-four years, and the arrival of four grandchildren brought Henderson-James’s life into balance. Her grandchildren remind her that the prime reason for family is to nurture and love, and to appreciate each one’s unique personality. They remind Henderson-James of the pure joy inherent in participating in family life.

From her grandparents, to her parents and surrogates, to her children and grandchildren, Henderson-James follows the family arc and discovers a way back to family integration.

The memoir is as thoughtful as it is lucidly composed, and the author’s life has been a fascinatingly memorable one.

In this part-memoir, part-parenting book, the author describes how the parenting style and family life of her missionary parents shaped and affected her, and how other people in her life contributed to the person she came to be. Her mother and father spent years in Africa helping children, while she spent years apart from them in dorms… Thankfully, Henderson-James found the care and nurturing she needed to fill that void, from alloparents (non-biological caregivers) and is able to help others in similar situations… Henderson-James tells her moving and thought-provoking story in ways that are factual and precise, without being harsh… All My Parents:Seeking a Sense of Self in Family is the book to read if you’re searching for the meaning of family and our place in it.

Among the growing number of books examining the effects of a globally mobile childhood, All My Parents takes a deeper look into issues of attachment disruptions. What happens to not only individuals, but family relationships themselves when there are frequent changes in family patterns due to mobility? Although some may say that since most children do not go to boarding school as Henderson-James did, these issues are moot, the truth is that the results of insecure attachment–for whatever reason–are not moot. For all who have lived globally mobile lives, or grown up in families whose parents are divorced, or worked with children of refugees, foster kids, or any other number of ways attachment patterns are interrupted, this is an important book. It reveals how such a story impacts the deepest places of a soul and family relationships. I highly recommend it.

All My Parents is soaked in light and shadow, insight and loss, as migrating families cross oceans and continents to empower the powerless leaving their own children, parents and families. Fueled with personal observations, pithy and lyrical writing, Nancy Henderson-James journeys back to examine the meaning of family roots and broken branches. She uncovers dark national and personal histories, tunnels through legacies of disability, economic disparity, veins of despair and moments of uplift. Always clear-eyed, evaluative and honest, Henderson-James’s fresh, original story of a traveling childhood from the U.S. to Angola to Southern Rhodesia, open her to a world of new languages, cultures, friends and caregivers but rock her growing identity with disconnection in her closest relationships. Regret pervades but hope endures in new relationships and possibilities. Expect deep, personal revelation and integrity, shocks of injustice set against moments of romantic uplift. Well-researched and narrated throughout, the disconnections in family relationship deliver a tragic lesson for the reader. Great personal sensitivity layered with human experience will make the reader cling to these pages.

All My Parents: Seeking a Sense of Self in Family offers a poignant account of Nancy Henderson-James’s formative years spent as the child of American missionaries in Africa. While her childhood was enriched with travel and carefree days on the beaches of Angola, parental nurturing was often spare and eventually supplanted with boarding schools and long spans of time under the care of surrogate parents. Henderson-James draws from these often lonely experiences, to describe how they impacted her life choices, family relationships and sense of self. She not only underscores the importance of parental presence and support but also how non-biological parent figures can serve as anchoring and protective factors. This insightful memoir also shines a light on the unique experience of missionary children and perhaps those who spend long periods of time separated from parents and siblings.

Excerpts

My Mother: Muriel “Ki” Woods Henderson

My mother was supremely capable, organized, energetic, and sociable, the perfect person to run a hostel and work as a missionary. She orchestrated the labor necessary for a smooth-running household with a hundred or more guests a year, managing the routines of our Angolan helpers. In times of high guest count, did we need an additional laundry lady to keep up with the hand scrubbing and ironing? Did our housecleaners have the supplies they needed? Did the cook have enough potatoes and carrots for the evening meal or did Mom need to drive over to the market? Were the hedges trimmed and weeds pulled? She taught her four children for periods when we weren’t away at school. She loved adventure and travel, following her father’s example, and her four children have taken a cue from her. I hardly recall a time when my father traveled with us to or from Angola. Mom corralled us on ships and trains, and drove us across the U.S. as the solo driver, stopping along the way to visit supporting churches, cousins, or friends. She was devoted to the larger family, community, and church, organizing materials for Sunday schools, nursery schools, women’s groups, and catechists. The “missionary barrels” in our garage, trunks in reality, were the source of pencils and crayons, thread and fabric for sewing groups, and clothing for children or beggars. They were filled with donations from sponsoring churches and also items Mom had purchased to see her family through the five-year term we’d be in Angola. She was truly an admirable woman.

But my mother and I had a vexed relationship, perhaps typical of mothers and daughters, though magnified by our special circumstances. In the patriarchy of Portuguese Angola, I didn’t recognize her valuable qualities when I was a child and teenager, but which are now so evident to me. I saw a woman less valued by society than my father and thus less valued by me; a Portuguese speaker who caused me to cringe with embarrassment; a mother fearless about launching into a crowd who had little patience with her shy daughter. I was puzzled by her enthusiasm for family in the States when she easily sent her children hundreds or thousands of miles away to school. I knew she loved me, but I took her quick reprimand or impatience as disparagement. The years of living away from her, beginning when I was nine, played a part in my lack of confidence. I hated to be told I looked like my mother, though now I recognize our strong resemblance, not just physically, but in my practical approach to life. She was not a dreamer and neither am I. Like her, I am driven to deal with the issues before me until I find some clarity. I will never feel at home in a crowd as she was, but I value my friends and hang on to them despite long distances between us, using correspondence and visits as she did to keep in touch. Her embrace of people, Angolan, Portuguese, Canadian, American, or any other, showed me the value of relationship, loyalty, and acceptance of difference. Though I did not take on her religious beliefs, the values my mother lived by are much the same as mine. I am grateful my parents gave me a life abroad with a worldview I might otherwise not have. Though I lack the daring spirit of my mother, the travel I did growing up gave me courage to explore as an adult.

Clearly, she influenced my personality and character in ways I now appreciate.

My Father: Lawrence W. Henderson

Dad’s political influence on me was clear when I became active in the 1960s anti-war, civil rights, and women’s movements. His moral message was more complicated, more ambiguous. Dad unequivocally hated the effects of alcohol and tobacco on the health of a person and on society. After his death, I found a journal he had written in Portugal between 1986 and 1989 after they retired. The most revealing part dealt with his angst about my mother’s smoking cigarettes. He struggled to understand why she would smoke. “The irrationality of smoking with a heart condition pushes me to look for the reason for her smoking. One I keep coming back to—she does it to hurt me. This reveals my guilty conscience about my infidelity. I know I hurt her terribly in Bunjei and Fair Lawn.” He goes on to say, “I admit this preoccupation is very negative in my life because of the time and energy I spend on it. On an average day I must think or feel about the subject 20 X.” At the time he was in his mid-seventies, certainly a period of assessing one’s life as I am now. I experienced him, in general, as avoiding emotional conversations. Finding this journal allowed me to reevaluate my sense of him, especially in light of admitting his infidelity. “Obviously smoking when you have a heart problem is stupid, but lots of other things are stupid which don’t bother me at all. Probably my tension and depression because of Ki’s smoking is just as dangerous for my health as the smoking is for her.”

When I was growing up, he struck me as an ethical, honest, and principled man and I adopted his attitudes as mine. In 1961 at the outbreak of the Angolan war for independence, the mission board advised the women with children to leave Angola while the men and single women stayed behind. My mother took this opportunity to travel through Europe with her four children on the way to the United States. For the first time, at almost sixteen, I was confronted with watching my mother enjoy a glass of wine with the friends we were visiting in France. Though I was an experienced traveler, socially and morally I was conservative. I was shocked and sick to my stomach, probably much as my father had been about her smoking. Missionaries just didn’t do that, I thought.

It was a difficult time for all of us. Africa was my home and suddenly on a few days’ notice we had to leave, without saying goodbye to anyone. Uprooted, unsure how long we would be meandering around Europe, not knowing where we would go in America, I clung to what I knew for sure. Drinking wine was bad.

What I didn’t know then was my father’s involvement in a romantic relationship with a single woman missionary, who had stayed in Angola with the men. My mother knew about the affair and feared for their marriage. Forced to leave her husband behind, with no assurance their separation would be short, I think she took advantage of traveling in France to live it up a bit, to enjoy a glass of wine, and perhaps to pay back my father for his much more serious indiscretion. The moral ambiguity of hating smoking and drinking while participating in an extra-marital liaison had a lasting effect on our family.